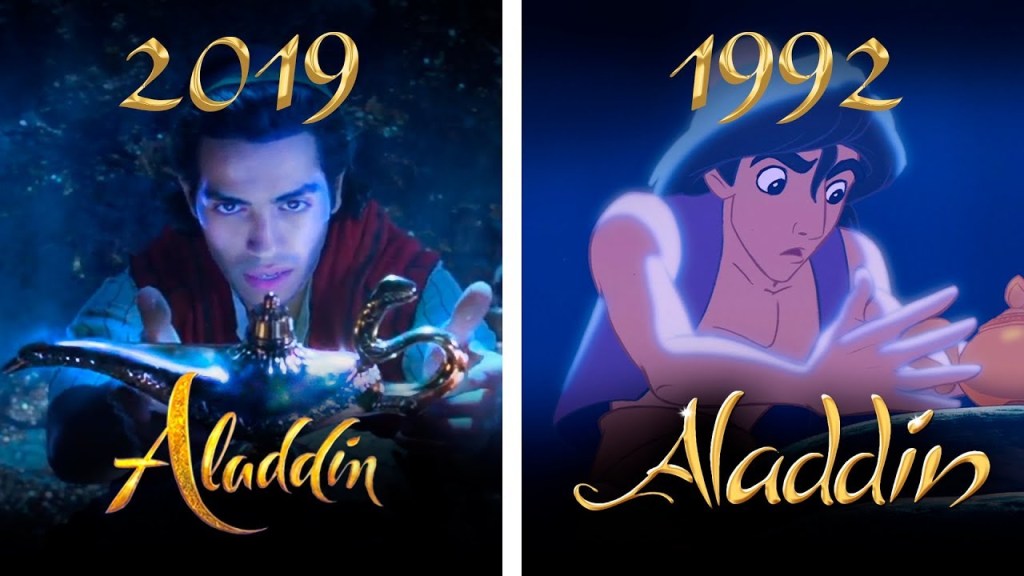

Using what we learned about Race and Gender Theories, I would like to analyse the Culture and Race Representation in Disney animated film Aladdin.

Synopsis

When Princess Jasmine, the lovely daughter of the sultan of Agrabah, meets Aladdin, a destitute but endearing street urchin, they become friends. Aladdin discovers a magic oil lamp while exploring her exotic home, and it summons a mighty, witty, larger-than-life genie. Soon after becoming friends, Aladdin and the genie must set out on a perilous journey to prevent the evil sorcerer Jafar from overthrowing young Jasmine’s kingdom.

The problem with Aladdin

The issue with fairy tales is that they offer parallel realities that clarify our own. They are sold by those who oppress us and are made to make us feel better about our privilege and ignorance. Although Aladdin is packaged as film that breaks diversity but underneath it describes how Brown people are a monolithic group of terrible people who must be subdued by Western imperialism and freed by white feminism.

Aladdin and Jasmine, for instance, speak with a very natural American accent, whilst the villains like Jaffar embodies a British accent. While Sultan and the guards attempt to imitate an Indian or Arabic accent, the rest of the town’s residents, including the salesmen, do the same. The characters are coded to support racist and Islamophobic stereotypes, and it mispronounces Arabic phrases, including “Allah,” and portrays illegible scrawl in place of authentic Arabic lettering. Jaffar’s curly beard, traditional attire, and “queer coding” serve as additional manifestations of his wickedness, whereas Aladdin is clean-shaven, mostly shirtless, and highly heterosexual. These kinds of audio-visual clues are absolutely not accidents. What’s more mind boggling is that, Aladdin is supposed to be inspired by Tom cruise.

The plot takes place in the ridiculous “Agrabah,” a country that is “barbaric, but hey, it’s home,” according to a line from a song so offensive that the next year, Disney rewrote some of the lyrics. Agrabah is essentially “Arabland,” a made-up region that actual Americans are prepared to bomb and which is rife with popular perceptions of the Middle East as a sand desert ruled by a violent Islam. Aladdin deftly escapes getting penalised for stealing in the opening scene after introducing us to the exotic climate through a seller with a thick accent who wants to sell us his goods. Later, he prevents Jasmine from experiencing the same fate—if you steal in a hostile environment like Arabland, you lose your hand. A major misconception about middle east laws and cultures are.

Disney may be facing harsh criticism for these misconceptions, but let’s not forget that the company was once a pioneer in creating stories that were exclusively about white people. Additionally, in its “biggest ethnic marketing campaign ever,” Disney sold the movie Aladdin to Black and Hispanic children in the United States. In order for a “Brown” story to be appealing to and represent all skin tones, Disney therefore conceptualises “Brown” as a monolith that may embrace Middle Eastern, South Asian, Black, and Latinx experiences making “representation” yet another irresponsible rendition of the Other. Christian society is implied rather than mentioned in contrast to the gruesome representations of a hybrid Arab-South Asian society.

The weaponization of oriental stereotypes by the West is misrepresenting Islam. “Whenever in modern times there has been an acutely political tension felt between the Occident and its Orient (or between the West and its Islam), there has been a tendency in the West to first turn to the cool, relatively detached instruments of scientific, quasi-objective representation,” according to Edward Said in his essay “Orientalism.” Without major adjustments, this movie is tacitly supporting Islamophobia due to the source material’s anti-Muslim bias.

“In this way, Islam is made more evident, the genuine nature of its threat revealed, and an implied plan of action against it is proposed,” Said continues. Between the timing of the movie during a huge rise in anti-Muslim hate crimes and the (mostly white) people behind the camera, it’s hard to be hopeful about Disney’s motives.

How to fix it?

A problem that cannot be resolved exists deep within the blatant orientalism of Aladdin’s scenery and cannot be separated from the plot of this boys’ adventure story. Jasmine is here. We are introduced to Jasmine, who has a very non-Arabic name that is yet oriental and feminine and was named after a non-Arab actress. She is undoubtedly a girl who is being forced to get married within three days of the movie’s start “by law” and by her Santa-faced, inept father. She serves as the blank canvas for white feminism’s portrayal of itself. She plays with caged birds while yearning for love in a marriage and doesn’t wear a hijab (unless when she pretends to be a poor and so “backward” Muslim). She is the “correct kind of Muslim”—a wealthy individual with few obvious cultural traits.

Jasmine has very little control over the narrative; her part in the movie depends solely on the males in her life. Her father, for example, reveals that he is pressuring her into marriage not just because it is required by law but also because he wants a man to “take care of her;”

Jafar, who at first wants to wed her for the power but later admits it’s just passion for young flesh; Aladdin, who spends the most of the film following her, even going so far as to break into her bedroom at night and pretend to be someone else.

Furthermore, let’s not forget the sex slave scene where Jasmine is restrained and seduces Jafar in what is undoubtedly BDSM material. What is the most egregious example of Aladdin’s intersectional misogyny? The lone female character is Jasmine. That is, unless you count the “loose” women and simple people who briefly appear in songs with bare-bones lyrics. Misogyny and orientalism work together to oppress women of colour in a special way.

A couple of years ago animators and voice actors began a campaign about to culturally accurate and rich the shows should be and the characters of such ethnicity should also be voiced by a person of the region rather than hiring a mimic. A successful feat and movement in itself. The 2019 live action remake of Aladdin retains the same problem. I believe it could be toned and rewrote grounded in actually reality rather than fantasy.

What strategies could I adopt to avoid biases in my practice?

It all boils down to research (documentation, conducting interviews etc) and spending time with people of those cultures rather than word of mouth (which most people do). Not all literature is accurate, so it is best to meet people in states and try to get a sense of their traits. Get frequent feedback etc.

References

Anon., 2019. Scholars. [Online]

Available at: https://scholars.org/contribution/how-racial-stereotypes-popular-media-affect-people-and-what-hollywood-can-do-become

Begue, L. et al., 2017. Video Games Exposure and Seism in a Respresentative Sample of Adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology.

Kini, A. N., 2017. Bitchmedia. [Online]

Available at: https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/problem-aladdin

Schacht, K., 2019. DW. [Online]

Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/hollywood-movies-stereotypes-prejudice-data-analysis/a-47561660